The Gary Green Family Tree ...

… an oral history as told by Gary Green

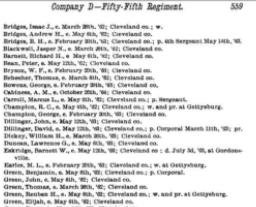

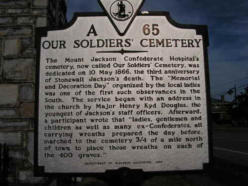

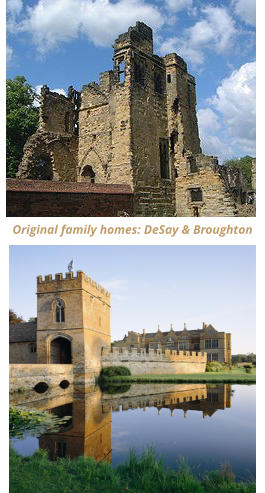

transcribed 2011 His pictures show a dignified, suited man with a long and sharply pointed nose, thin lips, big ears, a high forehead, and an egg-bald head except for thin gray hair at his temples. Actually, he sort of looked like my maternal grandfather in pictures from a decade later. George Northcroft was probably the world’s most prominent dentist in the first part of the twentieth century. Though a Brit through-and-through, he had graduated from the very- American University of Michigan in 1890 and then from the London School of Dental Surgery in 1892. He founded the London Hospital Dental School, wrote the British Dental Act of 1921 that made dentistry a profession, was twice President of the British Dental Association, and served as president of the European Orthodontic Society. He still is acknowledged as one of the fathers of modern orthodontics. Twelve plaster-cast masks that he molded of his son’s face from the ages seven to 21 are the oldest three-dimensional growth study in the world and today are an import part of the British Orthodontic Society’s museum. This cat knew his shit! It only made sense that in 1933 King George V would assign Doctor Northcroft, along with the similarly-noted anatomy professor William Wright, dean of the London Hospital Medical College, to conduct the forensic examination; a scientific query that, if botched, could rock the history of the monarchy. The charge was to conduct an identification autopsy of two sets of remains that had been safely hidden away since they were discovered in 1674; nearly two centuries after the deaths. Using state-of-the-art early twentieth century technology, measuring bones and teeth, the doctors forensically concluded that the remains were those of the legendary 15th century “missing princes of the tower”. Their not-too- startling conclusion had the side effect of vindicating my many-generations-back grandfather, John the Fugitive and ultimately planting my family in the American southeast. Decades before my birth and totally unknown to my family, the doctors’ vindicating conclusion, at least in the big picture, exposed the injustice in the loss of our peerage and eventual flight to America. The curious series of events intertwining the royal mystery and my idyllic Maginot safety began in 1066 (no, really), when William the Conqueror and the Normans fought the Battle of Hastings and were woven into both the Bayeux Tapestry and the history of the modern world. At William’s side was French Normandy-born knight, Robert Picot DeSaye. After the conquest of England, DeSaye was rewarded with the position Sheriff of Cambridge along with land holdings that would be listed in the Doomsday Book. The DeSaye family remained part of the land-owning lower peerage for the next 150 years until a DeSaye granddaughter upped the family’s standing by marrying Walter Sir Knight Lord Broughton, a genuine knighted member of the royal inner circle of Henry III and Lord of Broughton Castle. Still standing in the village of Broughton, the castle is about two miles southwest of Banbury, Oxfordshire, England on the B4035 Road. It has been featured in films: Oxford Blues (1984); The Scarlet Pimpernel (1982); Three Men and a Little Lady (1990); The Madness of King George (1994); Shakespeare in Love (1998); as well as television programs: Elizabeth The Virgin Queen; Friends and Crocodiles; Morecambe and Wise Christmas Show; Noel's House Party; and an adaptation of Jane Eyre. The modern Saye family still lives on the venerable old estate in my own personal lost Stately Wayne Manor. The couple’s oldest son fought with Edward the First during the eighth crusade …and died there. Nonetheless, they remained loyal to the line of Henry III and the Edwards and began a dynasty that would produce a chief Justice of the King’s Bench, a speaker of the House of Lords, several generations of high-sheriffs, a royally spurned outlaw and fugitive, a fighter in the American Revolution against England, a Confederate soldier in the Civil War, a long line of watch makers… and me. But that is getting way ahead of the complex intrigue. About the same time a disgraced great grandchild was leaving the UK to move to New Jersey, and 259 years before George V would call upon Doctor Northcroft, workmen were conducting repairs at the Tower of London. The workers dug down ten feet to reinforce a stairway leading from the White Tower to the Chapel of the then 599- year-old building. It was in digging for that new foundation that they discovered a small wooden box containing two sets of children’s bones. While the discovery of ancient bones in the half-millennium old structure was not particularly unusual, this particular discovery poured a Macbeth-like blood stain on the ancestral hands on the Crown itself. Immediately recognizing the potential damage to the lineage, sovereign Charles II ordered the bones sequestered to an urn and reburied at Westminster Abby inside the walls of the Henry VII Lady Chapel. Though the bones had been carelessly broken by the workers and mingled with rusty nails and chicken bones, speculation was that the small box contained the solution to a centuries old royal murder mystery and potentially verified the sky-is-falling warnings of my ancestor. Solved or not, the great architect Christopher Wren designed a small monument to mark the urn as the final resting place of the children of Edward IV, who disappeared in 1483. If the Wren plaque was true, then the final years of the restored reign of the House of York was illegitimate and made possible only through the murder of the rightful heirs of Edward IV. Confusing as all of that is to an American, in its “bottom line” it would mean three centuries of the British royal line had reigned only because of the murders of two children and the final resolve of the infamous War of the Roses. The War of the Roses was a thirty-something-year battle between rival branches of the Royal family. On one side were the supporters of the Duke of Lancaster, Henry VI, who at best suffered from some kind of mental breakdown and became oblivious to the world around him. On the other side were the supporters the Duke of York, Edward IV. During the 30 years of skirmishes, the Crown passed back and forth between York and Lancaster, Lancaster and York: Edward won the crown from Henry and kept it for nine years; then Henry won the Crown for less than a year before being either murdered or committing suicide. In 1471 Edward returned to the throne. My family, the titled, respected, and peered Knight Lords of Northampton and Broughton, remained loyal to the House of York because of their historical ties to the family. It was a support that would result in exile, imprisonment, and ultimately transplanting to America. A little more than a decade after Edward returned to the throne, poor health caught up with the 41 year old and isolated him to his death bed. Aware of his pending demise, the King named his brother, Richard Duke of Gloucester, as the royal protector of Edward’s twelve-year-old son and heir to the throne, Edward V. The protectorate proclamation also included Edward V’s brother (and his heir) Richard, nine years old. Shortly afterwards the king died. After the coronation of Edward V, but before he could be crowned, both boys disappeared. The disappearance was never solved and their protector, Uncle Richard, was crowned Richard III. The Legend of the Princes in the Tower remained enigmatic intrigue and royal gossip until Doctor Northcroft officially solved it. Unofficially, my family solved and exposed the murder plot before the boys were killed. Sir Lord John, son of Lord Earl Thomas V of Northampton, was widely regarded as the top sword of England and one of the Crown’s most trusted peers. A series of administrative records compiled in the English Chancery, running from 1201 to the present day, lists Sir Lord John as serving Edward IV and very specifically record his signing a warrant to take hay, oats, horse bread, beans, peas and litter for all expenses of the King's horses and litters for a period of six months. Clearly he was a trusted member of his majesty’s inner circle. After the death of Edward, the French spy Dominic Mancini routinely reported that he had seen the two orphaned boys playing in the garden at the Tower. Around the same time (nine years before Columbus’ trip and 137 years before the Mayflower’s arrival in the new world), Richard III summoned trusted Sir Lord John with a clandestine order and discreetly worded letter to the Constable of the Tower that he should put the two children to death. Though unyieldingly loyal to the House of York, John refused to order the execution of his mentor’s children. He reported back to Richard that the Constable had refused; and the King’s suspicions were never toward my rebellious Knight ancestor. The children, nonetheless, disappeared and were not “officially” located until 1933 and Doctor Northcroft’s forensic findings. King Richard rewarded John by significantly increasing his holdings and appointing him Receiver of the Isle of Wight, as well as overseer and escheator of the Port of Southampton. More practically, Richard needed John’s services to fight against two rebellions against the royal House of York, so the king took the additional step of granting John a royal pardon for all offensives, questioning about activities, or conspiracies during 1483 (the year of the children’s deaths). Apparently such pardons were not unusual during the aftermath of conspiracies. Swordsman Knight Lord John and the other warriors fought back and quashed an assault from the Duke of Buckingham; however the forces of Henry Tudor were more formidable. Against Henry, King Richard was killed in a battle, and his body was lost until 2013 when DNA testing confirmed that a body found a year earlier was indeed the slain king. The 2013 autopsy revealed the two mortal wounds to the back of the skull but eight other wounds: four to the top of the skull; one dagger stab through the cheek; one cut to the lower jaw; a cut on a rib bone; and a pelvic wound that was apparently delivered after he died. Reports from the battle described Richard being struck down, stripped naked, hung sideways over a horse and paraded into a crowd for final humiliation and additional jabs into his body. Henry Tudor took the throne as Henry VII and immediately married the sister of the two lost sons of Edward IV, technically uniting the two warring factions. Despite the unification, peace was not so tranquil; amongst the peerage there was still widespread belief that Edward’s sons had been murdered and that the House of York should hold the Crown. Henry set about to gain control of the situation through both direct and indirect actions. First he commissioned, with a very specific political agenda, Polidoro Virgili (often called the Father of English History) to write a history of the Crown in which Richard was further vilified as the murderer of the two children. More directly, he called for the arrest and issued a warrant for the execution of the loyal Yorkist John, by then known as Sir Lord John the Fugitive; John’s wealth was seized and the castle was awarded to the DeSaye side of the family, by the anglicized to simply Saye. Finally, he proclaimed himself King prior to the Battle of Bosworth where Richard had died (apparently kings can do such things). Like all great historical conspiracies, The Legend of the Princes in the Tower, spawned its own contemporary versions of the Kennedy Assignation, the 9-11 Perpetrators, Amelia Earhart, Judge Crater, Jimmy Hoffa, Christopher Marlow vs. William Shakespeare, the Shroud of Turin, CIA AIDS experiments, the death of Jesse James or Billy the Kid, the movie-studio moon landing, Mary Magdalene, or whatever uninformed pop culture of any epoch finds as “evidence”. One group argues, to this day, that the children were not murdered but secretly taken out of the pathway of the War of Roses; twelve-year-old heir Edward V was whisked away to Dublin where at 16 he was crowded Edward VI King of Dublin. Another group argues that it was actually Henry Tudor (rather than Richard) who offed the young boys at the insistence of his mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort/Stanley, who alleged conspired that in order for her son to smoothly take the Crown he would need to further vilify Richard III as murdering his own nephews. Alleged credence to the latter conspiracy theory is provided by the fact that Lady Margaret was BFF with the slain boy’s mother and the two of them arranged the murders to place the boys’ sister on the throne as Queen married to Henry. In either case, the record of Knight Lord John the Fugitive served to keep the conspiracies in the background and the prevailing legend of the princes in the tower alive. The doctors’ findings 191 later, were two centuries too late to vindicate my grand ancestor; he had to take of that himself. Though he fled to the ancestral homeland of Normandy France, John frequently returned to England to visit his family. Using the alias John Clarke, he repeatedly was able to visit unnoticed until one evening when he stopped at a Northampton tavern on his way to Broughton. A dozen or so rowdies were robbing the innkeeper at swords’ point, insulting the merchant’s perceived loyalty to York, and making advances toward his wife and daughter. In a real-life Douglas Fairbanks’ Zorro swashbuckling scene, the 38-year-old John drew his blade against the entire gang. Complete with swinging from rafters, jumping from table to table, and using candle poles as a shield, his fabled sword prowess was again proven as he singlehandedly challenged and defeated the entire gang and rescued the innkeeper. Unfortunately, few men had such legendary sword skills and he was instantly recognized as Edward’s most trusted Lord Knight. As word of the heroic encounter spread, “John Clarke” was forced to again flee England remain in France until after the death of Henry VII. Though nine years older than Henry, John outlived him by 11 years; Henry VII died of tuberculosis and his conniving mother died two months later. His first son and heir had died earlier, and the Crown then passed to his second son: the much maligned (and gluttonously rotund) Henry VIII. Important issues like beheading wives, creating a new church, claiming France, and neuroendocrine caused Type II diabetes… all kept the new King’s attention away from such mundane topics as who had refused to kill his royal great grand uncles four years before he was born. Consequently, Sir Lord John was allowed to peacefully return to his home, sans the “fugitive” moniker and with partially restored title. His oldest son, Robert, ambitious has his father if not as well connected, could legitimately argue to the Crown his linage from Sir Henry of Boketon, who had become the Lord Chief Justice of England under Edward III. However, drawing on the younger sons of his ancestral line (rather than the traditional “heir-at-large”), young Robert claimed conjugal lines to Charlemagne, Alfred the Great, and William the Conqueror. Unorthodox as such linage paths were for the peerage, by modern social probity, the linage was probably accurate (and is, incidentally, the basis for my own claim to the Doomsday Book family properties and William I). It also was sufficient for the Crown to re-knight the line and bestow the title Sir Robert Lord Bowridge on the fugitive’s son; a title which was also able to pass along to his son. In the Southern part of the United States we have a saying about seemingly unrelated information: “what does that have to do with the price of cotton?” In this case, it has everything to do with the proverbial price of cotton, because it is those two murders that ultimately facilitated my being here today. .

© 2017 The Gary Green Companies

Ever since the 1970s’ success of Alex Haley’s

Roots, it has been a part of pop culture to ask (or

speculate) on one’s ancestry; hence here is Gary

Green’s contribution to that taste of personal pop

culture. Above are 8mm home movies shot by his

father from 1956 through 1964. Gary notes, “I can

think of few things less interesting than home

movies”.

As for those roots, I am always amused at the speculation, friends, and even interviewers trying to guess cultural

history. Sometimes it is fun to let them believe what they want to, and just play off of that. Sometimes it is equally

fun to burst their genealogical bubble and simply tell them that I am "a hillbilly"; though that particular line didn't

go over well working for Donald Trump or other real estate moguls in New York City. People see the name "Green"

and immediately assume that it was shortened from Greens-tein or Green-berg or other Jewish heritage. When I

add the information that my father’s family was a long line of watchmakers and jewelers, that seems to confirm

those stereotyped assumptions. I also frequently hear from speculative observers that I must be Irish because I

have blue eyes and was born with red hair (that later turned blonde and then brownish before salting itself gray). I

have also been told by other wags that they are 99% certain that I am Northern Italian for some host of supposedly

deductive reasons the generally seem to be more related to professions than linage. It seems only to disappoint

these genealogy pundits when I tell them simply “I am 100% Appalachian hillbilly and nothing else.”

In their skeptical disappointment and prognosticating about the lost Tribes of Israel, they obviously never listened

to me sing or play guitar on any of my albums or concerts. Otherwise there would be little doubt of that hillbilly

ridge-runner heritage; and I NEVER recite the back-to-the-doomsday-book heritage above. I really was raised where

it was wrong to cuss, but “Damned-Yankee” was neither a curse nor two words; where one stands up to both the

Star Spangled Banner AND to Dixie; and believe it or not, where some storekeepers place all their five-dollar bills

face-down in the cash drawer because they don’t want the face of Abe Lincoln looking up at them.

In 1851 a watchmaker from Person County North Carolina, Willice Green, married Priscilla Bridges; then, on

September 28, 1854 (100 years before my birth) they had a child who they named James Willice Green but called

simply JW. Nine years later, Willice was at Gettysburg with a North Carolina Confederate infantry brigade fighting

for the lost cause; after the war, he returned safely and continued watch making and farming. In charming North

Carolina dialect, on JW’s death certificate, 80 years later, his mother’s name was spelled “Pricilar”; gotta love the

hillbilly dialect. When he grew up, JW married Laura Humphries and on July 7 1885, they produced Cleon Augustus

“Gus” Green in Ellenboro North Carolina -my grandfather.

JW followed in Willice’s footsteps as a watchmaker as did Gus and in 1918 the father and son opened Green’s

Jewelers in Roxboro North Carolina. A true family business, Gus’ cousins and nephews trained under him to

become master watchmakers and jewelers…and the business still exists today in its fifth generation of Green

ownership —though I have never met any of them and I doubt if they have ever heard of me other than via social

media.

Gus Green married Mary Collette, daughter of Callie Hudgins and her husband John Collette, a cotton mill worker

from Union-occupied Civil War Militia District 792 (between Cherokee and Cumming Georgia and about 45 minutes

north of Atlanta). They had three children, Festus (who was born when Mary was 22) and my father, Joseph who

was born 12 years later. A third child died at birth. Mary Green died on July 3rd 1930 before Joe was four years old.

Unable to raise a three-year old boy alone, Gus soon married Virginia Biggerstaff. Rare as it was in the 1930s for a

woman to be a working professional; Doctor Virginia Biggerstaff Green was a chiropractor. My mother told a

delightful story of the first time she visited my father’s house, she opened a closet door to hang up her coat and

found —literally— a skeleton in the closet.

By the time Joe had turned 16, Gus was in Baltimore being treated for a massive (and family-lore unexplained)

blood clot (arterial thrombosis) in his left arm. North Carolina doctors were mystified as to how a routine cut had

advanced from a mild gangrene to a massive clot. In those pre-penicillin days, the only hope was miracle medicine

being performed at Johns Hopkins in east Baltimore. Unfortunately, the prognosis was not good and on May 15

1941 sixteen-year-old Joe Green was again orphaned…left only to his stepmother.

Knowing his death was inevitable, Gus turned the family business over to the nephews and cousins that he had

trained. And too young to be part of the family business, young Joe Green hit the road from rural North Carolina to

join a traveling carnival.

Touring with a band of carnies he learned where to put the weighted bottles in the baseball throw; when to hit the

vibrator for the ring toss; how to position the plates for the coin flip; how to switch the sharp darts for the dull ones

for the balloon pop game; how to comb the hair up on the cat racks so the sucker can’t tell where to throw the ball;

…and dozens of other side-show swindles…er…I mean games. He learned that if he got into trouble to yell “hey

rube” and an army of carnival goons would come to the rescue. He learned that to send him mail the writer just

needed to address it to his name in care of Amusement Business Magazine Nashville Tennesse and it could be

forwarded to him whenever he requested it on the road. He learned all the tricks, frauds, and scams of the bearded

lady; the snake girl; the gorilla man; the smallest person in the world; the largest horse in the world; and all of the

midway sideshows that thrilled small town chumps and their families. He learned to watch the yokels step right up

for one thin-dime, one-tenth of a dollar to see this wonder of the world.”

Truly, in my own childhood, going to state fairs or traveling carnivals was an amazing experience. My father would

either explain why I should not play a certain game, or he would simply play it and win for us. While other kids were

begging their dads to let them toss the baseball at the cat pins or shoot the over-inflated basket balls into the too-

small hoops, my father was reaching under the counter and asking the carnie not to hit the vibrator to move the

pins when I tossed the ring. And to make it all even more cool, he spoke to them in some kind of special carnie

secret-code language that indicated he was a member of their special club. It was just too cool.

But most importantly in my father’s youthful “runaway and join a carnival” adventure, he had learned to deal

blackjack to the locals who would flock to the “back room” at various side show tents. He learned all the gambling

games and how to cheat the locals out of their money (and yell “hey rube” if he got caught). He learned to double

talk, to short change, and every card mechanic’s trick available on the 1942 carnival circuit through North and South

Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Virginia, Kentucky, West Virginia, Alabama and the other states on the circuit. At 16 he

was a genuine card hustler on the payroll of a traveling carnival.

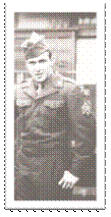

Three years later (and four months before his 19th birthday) as part of the generation that saved the world, my

father was onboard a ship slated to be the first invasion force to hit the beaches in Japan. With high school

diploma in hand as soon as he had turned 18, in December of 1944, he had attempted to enlist in the Army Air

Corps. A previously undiagnosed heart murmur kept him from flying; indeed it was the same heart murmur that

would lead to open heart surgery 35 years later and that I may have inherited myself.

But America was at war and on March 30, 1945 (a year after D-day, two months before VE Day, and almost six

months before VJ Day) the US Army’s 165th Infantry Brigade accepted his enlistment “for the duration of the War or

other emergency, plus six months, subject to the discretion of the President or otherwise according to law”. At 5-

feet-and-six-inches and 160 pounds, his enlistment document showed his occupation as “Civil Occupation: Car

Mechanic, Railway or Locomotive Mechanic or Signal Mechanic, Railway or Salvage Inspector (Salvage engineer).” It

also listed his educational level as “four years of high school” … which was a slight lie since North Carolina only

offered 11 grades instead of 12 back then.

He had worked most recently for the Seaboard Railroad and had developed an interest in the work of an

electrician. In fact, his first choice had been the Army Corps of Engineers; but every able-bodied man had been

assigned to the infantry to hit the beaches of Japan. If the invasion was successful, and if he lived through it, there

was a tacit promise from the Army that he would be transferred to the engineers.

The Japanese invasion was planned to be a Normandy-style top-secret “hit the beaches” campaign. The blood bath

was expected to surpass the 5,100 allied troops that had died on D-day on the beach in peninsular France. Literally

less than a week from the assault, on August 10th 1945 the ship’s Captain announced to all hands that (as my

father understood it at that the time) “some feller named Adam (atom) had made this real big bomb that was so big

that when Truman dropped it Hirohito and Tojo just gave up.”

Spared likely death during an invasion, 18 days later Joe Green became part of the first allied occupational force of

Japan. And, just a few months later he was transferred to the Corps of Engineers, given the rank of Sergeant, and

on the way to becoming a master electrician.

After the war, instead of returning to the road life of a carnie, Joe Green went to work in his army-trained

profession as an electrician. He signed back on with the Seaboard Airline Railroad as a signal maintainer riding the

rails from the station yard in Hamlet North Carolina down to Winter Haven Florida. Seaboard operated, among

many other trains, the main passenger line from New York to Florida: the sleek and high speed Orange Blossom

Special.

Immortalized in the great fiddle tune written by Ervin T. Rouse (and later made famous by Johnny Cash) that train

was the primary transportation for Northeastern snowbirds and tourists visiting Florida.

Joe Green was in Seaboard’s Jacksonville Florida dispatcher station one night in 1949. The stationmaster had been

watching the wall board that tracked train locations. Under normal conditions, as a train traveled along the rails it

would trip a signal every few miles; that signal would turn on a light on a map board at the stationhouse. By

measuring the time between two lights along the way, a stationmaster can not only determine the location of a

train, but its speed and whether or not it is on time.

On this particular night, one of the lights came on and when the second light was schedule to come on 15 minutes

later nothing happened. A half hour later, still no light.

My father was a signal maintainer; chances were that he needed to go out and see what might be wrong with the

signal… but on this night the dispatcher held him back. “I don’t have a good feeling about this; there is something

wrong with my Orange Blossom Special,” he told my father.

They waited for the time that two more signals should have been tripped, and still no light. As my father began to

analyze the possible causes of such a malfunction (simply shorting out the signal would have made the light come

on and stay on), the phone rang. An old farmer, obviously hollering into an old-style phone was so loud that Joe

Green could hear him even through the phone was in the stationmaster’s hand.

“Is this the Seaboard Railroad? Mister your Orange Blossom Special is wrecked all over this swamp and there are

bodies all over my orange grove,” my father heard.

As popular as the Rouse/Cash song became, I always meant to write a song about that great train wreck; no one

ever has. By the time you are reading this, I might have done so.

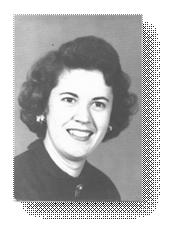

Dorothy Helen Mosley first saw Joe Green, from nearby Ellenboro, when she was about eight years old and he was

ten; he was carrying a stack of comic books.

From the tiny mountain cotton mill town of Caroleen North Carolina, my mother was a church pianist and a music

teacher in the same school she had attended a decade earlier. She was one of several rotating hosts of a local radio

show featuring her piano playing and performances by various school-age kids. She had (rare for a woman) a

college education, and a following of private music students in addition to the public school students.

An only child (though her mother had 11 brothers and sisters), her parents had both worked in the textile mill. They

bought supplies at the company store. They banked at the company-owned bank. They lived in a company-owned

millhouse across the street from the cotton mill and the dead-end railroad line that brought the cotton to the mill.

They had telephone service on the mill’s phone exchange. Except for my grandfather’s barber shop, they lived

totally at the pleasure of the owners of Caroleen Mills.

My grandmother quit her job to raise their daughter, and my grandfather went to work every morning at 6am and

got off work at 2pm. He would change from his overalls to slacks and short-sleeve white shirt, have lunch with the

family, and then open his barber shop until 9pm every night. Such was life in the mill town into which Dot Mosley

was born and raised.

Much earlier, in the late 19th century, during the heyday of the North Carolina textile industry, it was common for

mill owners to name their mills for female members of their family; and the towns supporting the mills adopted the

mill name. Consequently, North and South Carolina are sprinkled with little towns with names like Henrietta, Holly,

Latta, Caroleen, and so on; towns that at the time were no more than company stores and millhouses. The town of

Caroleen was founded in 1895, and named for the mother of one of the owners of nearby Henrietta Mills (named

for the mother of another of the owners).

Dorothy Helen Mosley (Dot, as she was called) was born in Caroleen in October of 1929 (just weeks before the stock

market crash) to Myrtle Murray Mosley and her husband Harry Thomas Mosley a loom mechanic and the town’s

only barber (and —straight out of an old West movie— keeper of a public bath tub).

Dot's maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Short Murray, was known throughout the southern Appalachian mountains

as a “good witch” with the biblically-mystical powers of making warts disappear, taking the pain away from burns,

curing incurable disease…and anointed by God to name unborn children. (Amongst my favorites of her naming

conventions were the twins, “Palmer” and “Chalmer” — pronounced with a short “ă” as in pal and chow.) I

remember seeing her a few times before her death in 1957; she always dressed like a Pilgrim: long black cotton

dresses with handmade white lace collars around her neck. She had promised to pass the “secrets” of her holy

magic along to my mother but “lost her mind” (apparently from Alzheimer’s; she died of a cerebral hematoma)

before her death at 95 years old.

Elizabeth Short, the witch, was married to George Washington Murray Jr., a mill worker who official records report

died at 56 in 1924 but whom my mother (born in 1929) clearly remembers. They had twelve children named for

flowers, for Romeo and Juliet, and a half-dozen other monikers of witchingly divine providence. My grandmother,

Myrtle Rose, born in 1898, was neither the youngest nor the oldest of the litter.

My grandfather, Harry Thomas Mosley was born in 1901 in rural South Carolina to Elzie Van Mosley (born in 1869)

and his wife Willie Belle Butler. Census records report that Elzie was a farmer and “mill hand” but family lore is that

he made his money from royalties on patents for farm machinery and improvements in existing farm machinery. A

search of the US Patent office records finds no mention of him; but that would not be unusual. In those days (and

many long years afterwards), inventors (like songwriters) sold their inventions for either a flat fee or a “royalty

schedule” and gave up all claim of being the creator. The Mosley family all concur that Elzie was an inventor for a

living.

Elzie’s parents, Hecter (sic) and Elizabeth Gibson Mosley also had deep roots in the southern Appalachian

mountains. Like the Green's and the Murray’s they were Confederate, Baptist, and pure “hillbilly”. So the marrige

was as Southern as one can get.

Harry and Myrtle Mosley were deeply religious and leaders in their local Baptist church. During the great textile

strikes of the 1930s, Harry T. Mosley crossed the picket lines, scabbed on his co-workers, and then turned around

and used his wages to run free soup lines out of his home to feed strikers. The braided paradoxes of “mountain

folk” is more twisted than fiction could tell.

Their only child, Dot was raised in the church, became a church organist, and attended an even more-rural and

isolated mountain college run by the North Carolina Baptist Association. Unlike neighboring Bob Jones University

where prospective graduates were required to stand on street corners and preach to passersby, Dot’s college was

so rural there were no street corners. One of a few, but growing, number of college-educated women, Dot was on

the road to a life as a church organist. (And her parents always had high hopes for me to become a fiery Baptist

preacher.)

As my father later noted, “the only thing wrong with the Christians is that they cut back on the lions about 2,000

years too soon.”

The southern parados continued. The Civil War was 70 years in the past by the 1930s, but it was still the pre-LBJ

deep South with not-so-subtle nor faint racism. While my grandparents certainly could not have had slaves in the

twentieth century, they did have African American “help” (servants) who (not so) coincidentally shared the same

family name; apparently they were decedents of the Mosley family slaves.

Inez Mosley, the family “mammy” and “help” was still working for my grandparents well into the 1950s that I can

remember. She used to tie knots in the four corners of a handkerchief and wear the cloth as a sort of slave-style

cap; many times since then I have created such caps for myself when working in the hot sun. That is the only pearl

of wisdom I can remember from Inez; she was old and I was a toddler.

My mother, in a “Driving Miss Daisy” moment, once told me “we always invited Inez to sit down at our table and eat

lunch with us just like anybody else.”

It was a different historical epoch than the 21st century and THAT gesture was an amazing liberal if not out-and-out

radical behavior for the 1930s’ deep South. Far beyond accepted “Christian charity” it was pure extremism and

raised the eyebrows of all the “good white people” in the community. Well into her eighties, herself, my mother

recalled "I didn't care what people thought."

The more rural pockets of the old South, like Caroleen, were still living in a time that was, at best, a generation or

two behind the rest of America…which was itself insanely backwards by modern standards. (Though the original

Ku Klux Klan had died out in the 1870s, there was a huge resurgence of organized hatred in the 1920s as Klansmen

openly served in state legislatures, US Congress, and governors of several states).

The culture of the ruling class of any epoch of history, always becomes the prominent popular culture…even (as

history has shown many times) when that culture serves to oppress the ones who adopt it the strongest. For

example, just look at the most rabid pro-war forces in the 1960s, the Ronald Reagan supporters of the 1980s, even

the George W. Bush supporters of the early 21st century. And Inez Mosley actually did call her own grandchildren

“pickininnies”.

The apple indeed sometimes must fall a long way from the tree; who would have ever thought that Harry and

Myrtle’s oldest grandson would be marching in Civil Rights rallies throughout the South, playing guitar and leading

crowds singing “We Shall Overcome” alongside Ralph Abernathy, Hosa Williams, and arm-in-arm with Coretta Scott

King?. What audience of marchers and protesters would expect,in the same concert, to hear Hank Williams songs,

Pete Seeger tunes, and Gary Green originals? Yes, the apple may fall far from the tree; but clearly the paradoxes

continue.

Music teacher and semi-celebrity (at least locally) Dot Mosley apparently had a host of suitors, but Joe Green

continued to court her over the years and in 1950 they eloped to Atlanta. Four years later, I became the firstborn of

three boys.

Clearly my mother’s music and the rich mountain gospel roots (though she is quick to point out it is not “holy rolly”)

taught me to rock & roll and be a radical. After all, she was the one who put me in front of that black and white

television to see Jerry Lee Lewis on the Steve Allen Show.

But if Dot Green taught me to rock and roll, it was clearly Joe Green that taught me about gambling…and a lot

more.

Railroad families got to ride for free; and on the trains I learned the meaning of all the signals and even how to

stand by the tracks and give hand-signals to the caboose to tell the workers they had a smoking hot box or other

problem. (Old railroad car axels were connected in a box that was padded with wet cotton. When the cotton would

dry it would sometimes catch fire, beginning with smoldering. Railroad yard employees would signal the caboose

that they had a smoking hot box, so they could put more water in the al box.)

But by the time my two brothers were born (1958 and 1961), my father had left the railroad, taken his electrical

skills to other venues and was starting to apply some of his old carnie skills as part salesman and part installer of

commercial electrical products. After General Eisenhower was out of office and America embarked on a New

Frontier, Joe Green also embarked on a new life, finally melding his carnie-days skills and his people skills to step

into the world of sales and the sales management.

By bother Ron was born on Valentine's Day in 1958. On the way to the hospital to bring him and my mother home,

my father hit the brakes to avoid a collision. I tumbled from where I was playing on the back seat to the floorboard

of the car and snapped my collarbone. For decades, my mother enjoyed telling the story of getting a call from my

father saying “I am going to be late picking you up, I have to take Gary to the emergency room.” He explained

nothing beyond that, and hung up the phone. In the 21st century Ron teaches at a university, holding a PhD and a

couple of Masters. His two children, Mary and Daniel seem to be the only next generation of the Greens.

Our brother Keith was born in February of 1961. Keith is the big (well over six feet), stable, normal one of the three

Green boys of our generation. He owns a residential construction company, is a private jet pilot, and lives in a large

home that he built.

As soon as each of the three brothers could hold "hold" a deck of cards, he taught us how to "magician's force" a

card to the top of a deck, how to deal seconds, how to spot a cheat…and the most important childhood lesson:

never burn a face card.

Thanks to his training, by age 12 I had been thrown out of my first casino; well, first thrown out and then offered a

job a shill by a bingo hall (a wanna-be casino) in tourist-Mecca Myrtle Beach, South Carolina during a family

vacation. It seemed that I had been finding, collecting, and playing the hot cards all night, every night, for a week.

Traveling with my father on his sales routes I spent hours exploring small towns in Eastern Kentucky, Western

Virginia, East Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia, South Carolina; towns like Martin, Melvin, Pikeville, Harlan,

Hazard, Elkhorn City, Wise, Haysi, Bristol, Kingsport, Church Hill, Johnson City, Jonesboro, Gate City, Big Stone Gap,

North, Buford, St. Paul, Kingston, Harriman, Abington, Cherokee, Chimney Rock, Bat Cave…and the list goes on and

on.

I wandered the main streets and alleyways in every one of them and more. I can’t EVEN remember all the places

we lived; and I can barely remember all the places I went to school: East Point Georgia, Kingsport Tennessee,

Dekalb County Georgia, Nashville Tennessee, and Gastonia North Carolina; only five towns but eight different

schools.

So I would break open a new pack of bicycle playing cards for any group of kids anywhere. Shuffle and shuffle

again; then let any one of them cut and reshuffle. With the deck back in my hands, I would offer, “Pick a card from

the deck; any card; pick a card. Look at your card; show it to your friends, but don’t let me see it. Ok remember your

card. Now slide back into the deck.”

Using any number of cheesy magician’s tricks I would mark the location of the card or adjacent cards. Shuffle and

shuffle again. Position the card to the bottom of the deck and glance at it to identify it. At this point the “trick” was

over; it was just a matter of taking their money now.

“Here, you shuffle. Cut the deck. Shuffle "Shuffle" again. Now let’s turn the deck face-up and divide it into two

piles.”

I would count the cards, putting every second card into a pile at the right and the others into a pile on the left. All

the while, I would say things like, “I hope I can remember how to do this trick; there are too many card to make this

work, I am gonna use just half of the deck.”

The sucker would, of course, see their card and know if it had ended up in the left of the right pile. "Which pile do

you like best: the right one or the left one?”

If their card was in the right pile and they picked the right pile then I would say, “ok great; let’s use the one you like

then and throw the other one away.” However if they chose the other pile, I would say. “ok great; let’s save this pile

for later and use the bad one first.” Either way, we would end up playing with the half of the deck with their card in

it.

I would then repeat the process, dividing the remaining deck into two piles and forcing play with the portion of the

deck that had their card in it. If they started to catch on to my word tricks, then I would “throw away” the portion of

the deck with their card in it and continue to play with the remaining cards.

Finally, I would narrow the choices down to six or seven cards. I would ceremoniously pick up those cards and

shuffle them carefully. I would then discard, face up, three of the cards —making certain that one of the discarded

cards was their chosen card. With the remaining three or four cards I would again double-talk something about

how difficult this trick is and I hope I get it right. One at a time I would turn the remaining cards face up, until there

would be only one face-down card remaining.

All the while, the sucker’s chosen card was face up in a discarded pile. With great pomp, I would start to turn over

the final card and the stop, and announce, “I think I remember for sure how this trick works. I will bet you 25¢ that

the next card I turn over will be your card.”

Totally aware that their card was NOT the face-down card, most kids would take the bet, with the expectation of

taking advantage of my inept work and cheating me out of a quarter. Once we “shook” (hands) on the bet, I would

casually move my hand over to the discard pile and flip their card upside down, leaving the face-down card

untouched. In fact, the “next card I turned over” was their card. Twenty-five cents for me.

Okay, it was not a lot of money; but comic books were 12¢ and candy bars were a nickel. So for an eight-year-old, it

meant the latest issue of Batman or Detective and a Three Musketeers bar…with change left over. Living large; life

was good.

Good grief… I have talked enough for right now; maybe i should be planning my next book…

Gary Green, Spring 2011 (eight months before his parents’ deaths)

The Green Family Crest

The DeSaye Crest